Acid Basics

There are many types of acids contained in the coffee bean, and just as many factors that determine the strength and composition of those acids. Here we look at just a few of the more common organic acids and their characteristics in the roasted product.

There are many types of acids contained in the coffee bean, and just as many factors that determine the strength and composition of those acids. Everything from where the coffee is grown and its genetics, to how it’s processed, and finally how it’s roasted that influence the unique acid profile of each bean. This article will touch on just a few of the more common organic acids and their characteristics in the roasted product.

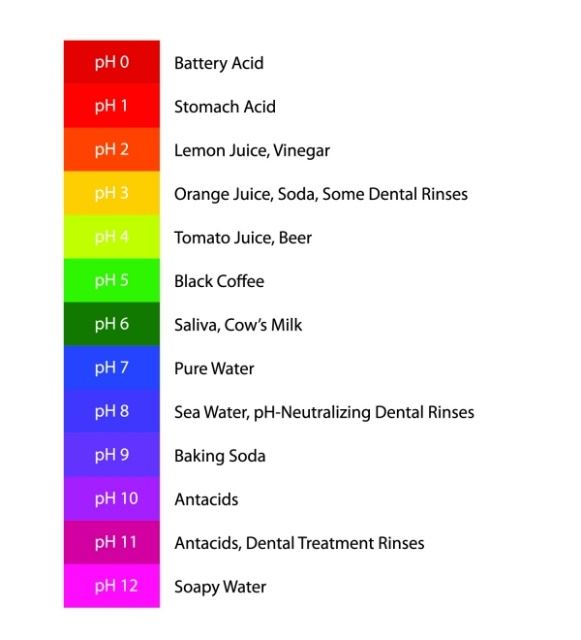

Acids in a cup of coffee are not always directly correlated to the acidity (pH) of the coffee. While coffee (Arabica) generally ranks about 4.8 - 5.1 on the pH scale, the intensity of acid as a flavour attribute does not really influence the pH. So a bright tangy Kenyan coffee will have a similar pH to a smooth mellow Brazilian.

To start with the basics, Chlorogenic Acids (CGA) make up the highest concentration of organic acids in a brewed cup of coffee; about 30% by volume. During coffee roasting, CGA’s progress through a number of forms which ultimately influence the flavour of the brew.

QUINIC ACID

Characteristics:

Bitter notes and a heightened sense of body/mouth feel. This acid is perceived

more when tasted at cooler temperatures (25 – 30°C)

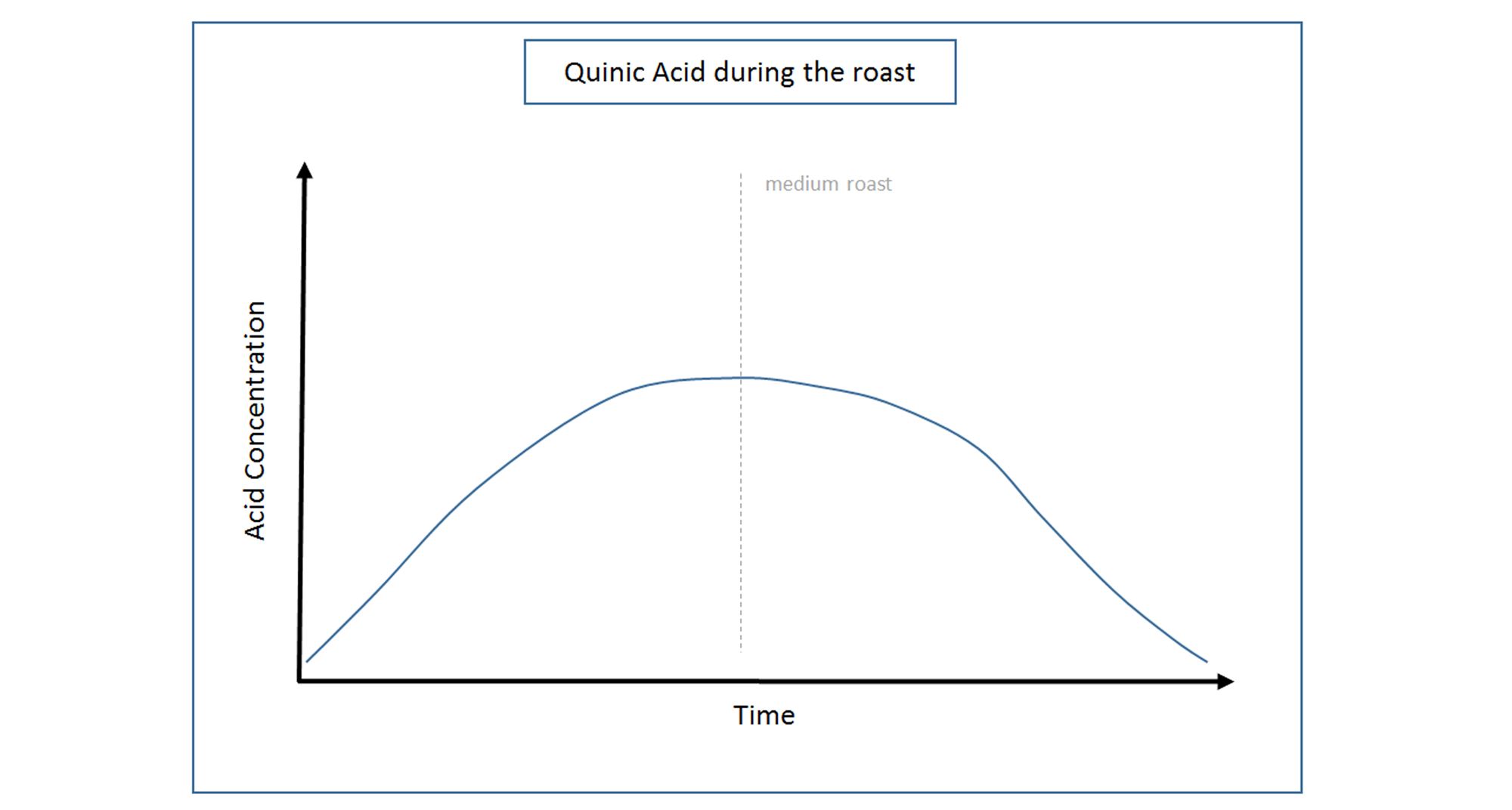

Initially, as heat is applied to the green bean during the roasting process, Chlorogenic Acid starts to decompose and generate Quinic Acid. It reaches maximum concentrations at a medium roast, but begins to break down itself after prolonged or dark roasting.

During a long roast, a secondary compound, Quinide (the bitter compound found in tonic water) is formed from the Quinic Acid. When left to stew in a hot infusion, such as a filter brew sitting on a hot plate for a lengthy period of time, Quinide can hydrolyse back to Quinic Acid, which, when tasted can be perceived as a very bitter, acidic and sour coffee. This phenomenon may also be noticed when cupping coffees on a cupping bench through a range of temperatures from hot to cool.

CITIRC ACID

Characteristics:

Sour, citrus fruit notes such as lemon. High bright aroma.

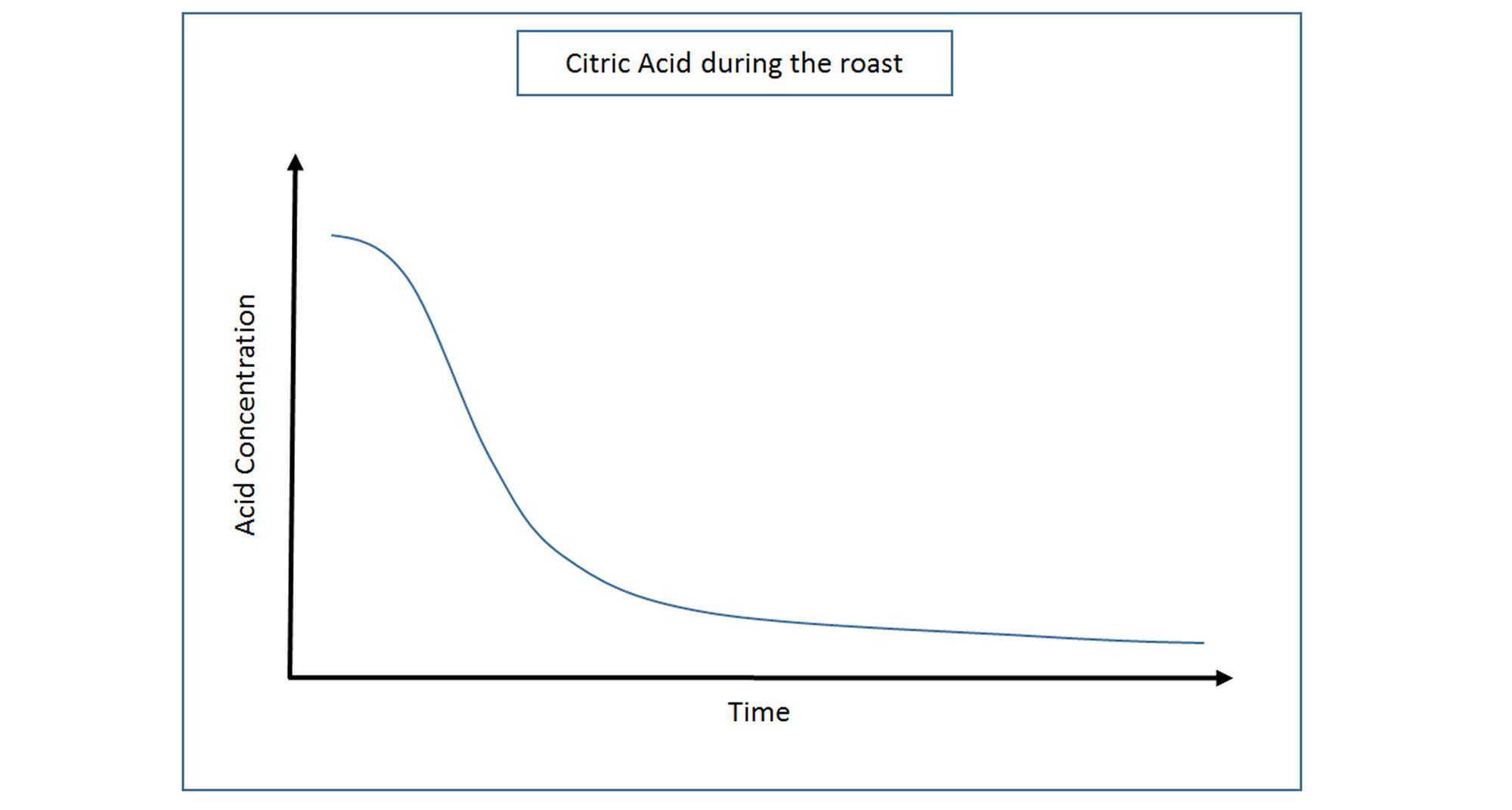

In green coffee, Citric Acid makes up the third largest portion of the total acid content behind Chlorogenic and Quinic Acid. Citric Acid is naturally formed within the beans on the tree and unsurprisingly, this acid’s concentration is found to be highest in the green beans before roasting begins. Interestingly, the more immature the coffee cherry is when it is picked, the higher the concentration of Citric Acid contained in the bean, therefore more sour notes can arise from under-ripe beans.

During roasting, Citric Acid very quickly breaks down to just 50% of its initial concentration at a medium roast, and less the further the roast progresses.

MALIC ACID

Characteristics:

Rounded yet crisp, but not sharp like Citric Acid. Provides more flavour than

aroma. Also found in high concentrations in green apples and cranberries.

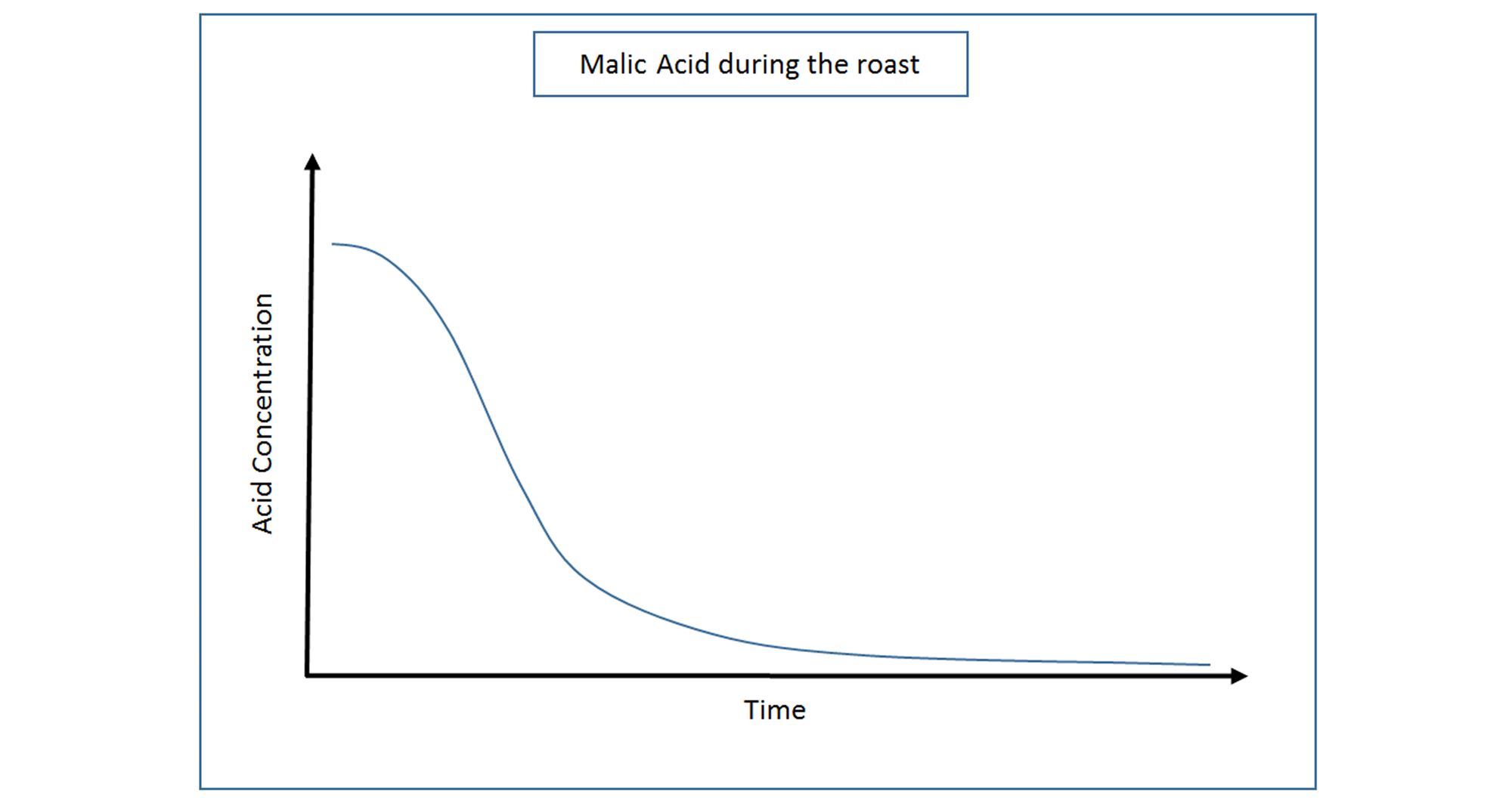

Similarly to Citric Acid, Malic is formed in the green beans on the tree, and is found in highest concentrations before roasting begins. Malic Acid also begins to degrade immediately upon roasting. Malic is one of the more delicate acids and often more difficult to detect on the palate.

ACETIC ACID

Characteristics:

Usually pleasant, yet tangy/winey with sweet clean notes – but can become

vinegary and ferment-like at high concentrations. Also easily detected

aromatically.

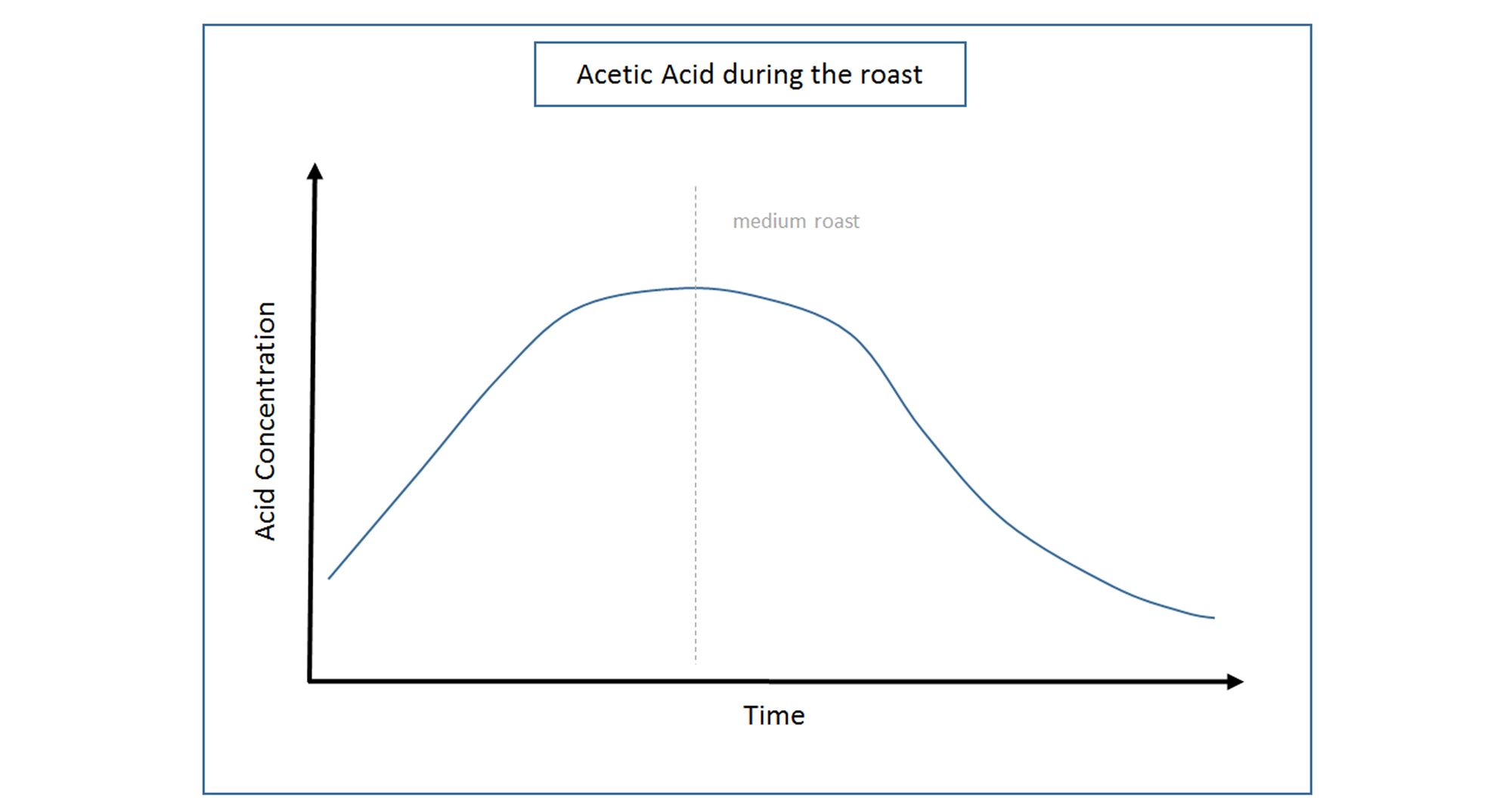

Acetic Acid is formed during the fermentation stage of green bean processing. Higher concentrations of Acetic Acid are found in ‘Natural’ or ‘Unwashed’ coffees when compared to their ‘Washed’ counterparts. This is due to an intense internal fermentation that occurs within the skin of the cherry of ‘Unwashed’ coffee, while ‘Washed’ types generally ferment in manual tank systems under a controlled set of conditions.

Unlike the previously discussed acids, Acetic Acid increases during the roasting process - up to 25 times that of its initial concentration in the raw green bean. Through the roasting, sugars contained in the bean begin to break down to form the acid, reaching their peak concentrations around a medium roast. However Acetic Acid is very volatile, and continued roasting can cause the acid to evaporate. This is particularly noticeable when comparing the flavour attributes of a light and dark roast of an ‘Unwashed’ fruity coffee (eg Ethiopia). The lighter the roast, the brighter and more winey the acid notes tend to be.

The best way to become acquainted with these acids and how they affect the cup is to try experimenting with different roast profiles. Try roasting the same coffee to differing degrees and tasting them in comparison. Alternatively, try tasting coffees of the same origin that have been processed by different methods. Continually tasting coffee helps to create a personal data bank of flavour and acid profiles.